Ancient TN ports had flourishing trade with Rome, Greece and China

Updated by admin on

Sunday, June 10, 2018 03:21 PM IST

Chennai:

India is currently worried about balance of trade with the rest of the world but at the dawn of the Christian era, South India in general and Tamil Nadu in particular had a favourable balance of trade with Rome.

Various ports along the Coromandel coast for example, and Puhar (Poompuhar) , Korkai, Mayilapur, Madrasapatnam and Pazhaverkadu had established trade relations with several foreign countries, and Tamil Nadu had a large share of exports to Rome.

So much so, some Romans were worried about the flow of currency to South India, says noted historian S Krishnaswami Aiyangar.

Petronius had complained that fashionable Roman ladies exposed their charms much too immodestly by clothing themselves in the 'webs of woven wind', as he called the muslins imported from India.

Pliny, who gives a description of voyages to India in the 1st century AD and refers to many Indian ports in his The Natural History, said that India drained the Roman Empire annually to the extent of 55,000,000 sesterces, equal to 486,979 pounds sending in return goods which sold at a hundred times their value in India. He also remarked that 'this is the price we pay for our luxuries and our women'.

Krishnaswamy Aiyangar says, "That Pliny's complaint about the drain was neither imaginary nor hypersensitive" is confirmed by a passage descriptive of Muziris in one of the ancient classics of Tamil literature (Ahananooru 149) : Musiri to which come the well-rigged ships of the Yavanas, (then a term for the Romans and later also included the Greeks) bringing gold and taking away spices in exchange.

Regarding the trade on the east coast, the following is a description of Puhar (Poompuhar or Kaveripoompattnam) as a port: "Horses were brought from distant lands beyond the seas, pepper was brought in ships; gold and precious stones came from the mountains; sandal and aghil came from the mountains towards the west; pearl from the southern seas and coral from the eastern seas. The produce of the region watered by the Ganges; all that is grown on the banks of the Kavery; articles of food from Ilam (Ceylon) and

the manufacturers of Kaalaham (Burma)' were brought there for sale. (Pattinalapaalai 127 ff. and the Tamils 1300 years ago, p. 27)

Important products that were received in the Port of Tondi were aghil (a kind of black aromatic wood), fine silk stuff (from China), candy, sandal, scents and camphor. All of these articles and salt were carried into the interior by means of wagons drawn by teams of oxen, slowly trudging along through town and village, effecting exchanges wuith commodities for export. Tolls were paid on the way, and the journey from the coast up the plateau and back again occupied many months. A brisk and thriving commerce with the

corresponding volume of internal trade argues peace, and the period must have been a period of general peace in the Peninsula. They did not forget in those days to maintain a regular customs establishment, the officials of which piled up the grain and stored up the things that could not immediately be measured and appraised, leavingthem in the dockyards carefully sealed with the tiget signet of the king. (Pattinappalai 134-6). (There are references to Tondi port near the Malabar coast and in Ramanathapuram district of Tamill Nadu, where it was believed to be an ancient port site of the Pandyan kingdom. A scheme to revive the Tondi port was also drawn up a few years ago as part of the Sethusamudra Canal Project (SCP) reportedly costing Rs 100 crore but with the SCP put on the back-burner by the NDA Government at the Centre, one is not sure if the Tondi port project would be revived at all).

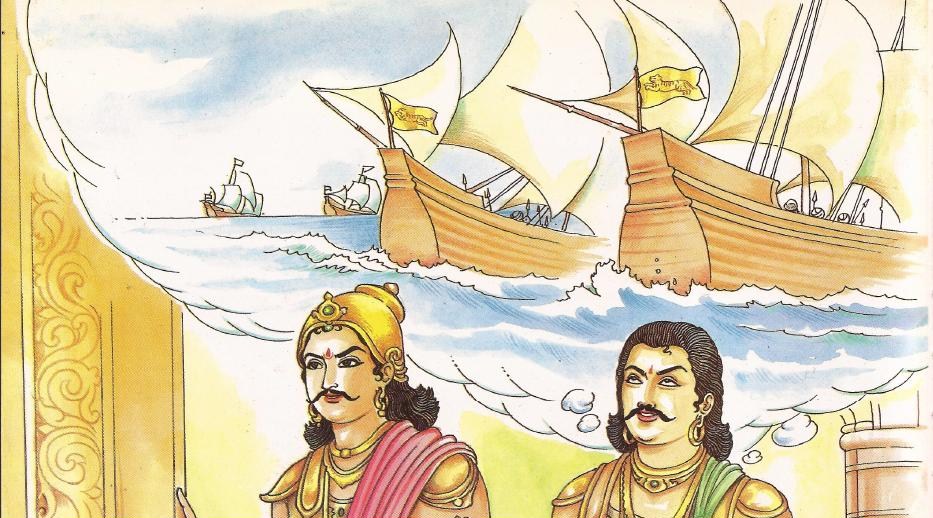

The Tamils in ancient times built their own ships; and in the other crafts of the skilled artisan they seemed to have attained some proficiency, though they availed themselves of experts from distant places.

Sewell, who has made an elaborate study of Roman coins in India, concluded that with Augustus, began an intercourse between Rome and India, which enabling the Romans to obtain oriental luxuries during the early days of the empire, culminated about the time of Nero who died AD 68. Friom this time forward, the trade declined till the date of Caracalla, AD 217. From the date of caracalla, it almost entirely ceased. It revived again, though slightly, under the Byzantine emperors.

Sewell points out that the trade under the early emperors was in luxuries; under the later ones in industrial products, and under the Byzantines the commerce was with the south-west coast only.

Historian P T Srinivasa Iyengar noted that extensive travels by land and sea in very early times can alone have made possible the colonization of the Mesopatamian valley by the Tamils, which gave birth to the ancient Sumerian civilization of that region. The Indian teak was found in the ruins of Ur (Mugheir) which was the capital of the Sumerian kings in the IV Millennium BC. The other is that the word Sindhu or muslin is mentioned in an ancient Babylonian list of clothing (Sayce, Hibbert Lectures pp 136-138)....the muslin went direct by sea from the Tamil coast to Persian coast, and the Babylonian word Sindu for Muslin is not derived from the name of the river (as has been supposed) but from the old Dravidian word, 'sindi' which is still found in Tulu and Caraese, and means 'a piece of cloth' and is represented by the Tamil word, Sindu, a flag. There is some evidence that the trade of South India extended to Egypt in the III Millennium BC. The articles taken to Egypt by the Arab intermediaries were South Indian ones and that South Indian Paradavar took them in their boats to Aden and the East African coast.

In the IInd Millennium BC, ebony was imported largely from South India by Egypt under the XVIII dynasty. Precious stones including lapis lazuli too came from South India. A little before the end of the second millennium BC, cinnamon, broughjt by Arabian merchants from India, was imported by Palestine as it was one of the ingradients of the sacred anointing oil of the Hebrew priests. They also procured sapphire from India.

There was ample intercourse betweeen China and India in II millennium BC. In Xth century BC, the Queen of Sheba gave King Solomon "of spices very great store and previous stones; there came no more such abundance of spices as these which the queen of Sheba gave to King Solomon". Most of these articles were said to have come from South India. "...the King made of the almug trees pillars for the House of the Lord" (these almug trees were identified with sandalwood, said to have moved from Coimbatore, Salem and Mysore to the Gujarat ports and from there to Syria via Arabia.

After 606 BC, the Assyrian Empire was overthrown and Babylon became the headquarters of trade in Asia. There was soon a colony of South Indian merchants established in Babylon which continued to flourish there till the III century AD.

The Greeks became the greatest intermediaries of Indian trade with Europe in the millenium before the birth of Christ. Consequently, Tamil names of South Indian articles of trade were borrowed by the Hellenes, appearing in the works of Sophocles, Aristophanes and others. They are Oryza from Tamil arisi; Karpion from karuva, cinnamon; Ziggibros from Tamil injiver/Sanskrit srngivera, ginger; peperi, from Tamil pippali, long pepper, Beryllos from vaidurya, which was mined in ancient times in the Coimbatore district.

After Augustus conquered Egypt in 30 BC, he established direct sea trade contact between India and the Roman Empire. Strabo says that in 25 BC, he saw about 120 ships sailing from Hormus to India. Augustus himself said that Indian embassies came to him frequently. Warmington believed that the Chera, Pandya and Chola monarchs of the time, sent separate embassies to Rome. Warmington adds, "From the very start, the Roman empire was unable to counterbalance the inflow of Indian products by a return of

imperial products, with the result that the Romans sent out coined money which never returned to them! A fraud was attempted.... They were possibly "struck exclusively for trade with South India where the natives (it was thought) could not as yet distinguish good Roman coins from bad". But the Tamils proved to be too shrewd, and the silly experiment was not repeated!

By R. Rangaraj